"days of our lives cast (1990)" (resized) by mtnbikrrrr (resized) is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Most soap operas have extended casts. There isn't a single main protagonist because there isn't just one story being told. Instead, stories involve a stable of major and minor characters, often in groups known as core families. In U.S. soaps (the ones with which I'm most familiar), episodes highlight different characters and their storylines on different days. Everyone gets their time in the spotlight, but they may have to wait their turn - rather like player characters in a tabletop campaign. Some storylines and characters will be at the forefront for a while due to the urgency of the tale at hand, but eventually, they'll take a back seat and other characters will get their time to shine. This is why they're known as front burner and back burner characters in soap opera jargon. Scenes will bring certain characters together for a while, break them apart, and reconfigure them as the overall timeline moves forward.

Keeping spotlight time in mind is a good idea in gaming for a few major reasons. First, giving player characters their own stories and focusing on them during particular scenes can engage them. This doesn't mean that the other player characters have to go away; it means zooming in on a particular PC's history, skills and/or relationships more often. This should be possible to some degree just about anywhere, but might be less helpful during combat, when characters need to work as a team. It can certainly make downtime something to look forward to, even if PCs have to wait their turn. Asking players what their characters will be up to after a big adventure can provide ideas for personalized scenes.

This can also be used to highlight particular NPCs, to a lesser degree. They might not get as much time in the spotlight, but brief interludes that feature key NPCs can give PCs the chance to learn about them. Imagine the party overhearing a conversation or noticing an NPC doing something suspicious. These scenes can also be unique and engaging ways to deliver plot hooks. Instead of consulting the quest board in a tavern, meeting an NPC in the stables at midnight can make it feel like more is at stake and anything could happen next.

One practice on soap operas that I've never seen in any other type of show is recasting a role out of the blue and in the middle of the action. Since, as I've said above, established characters are important to the whole, a soap opera might not want to write them off the series if the actor who portrays them wants to leave. Instead, the soap simply hires a new actor for the part and one day, unannounced, that actor is presented as the character. The rest of the cast responds to them as that character, and the story moves on.

I have to be honest: fans aren't always thrilled about these changes, and there's always a period of adjustment. Usually, the new actor resembles the last one, so changes to the character's appearance aren't terribly jarring (it's unlikely for a blond to replace a brunette, for instance). But each actor brings something different to a part, and some fans might not like the new actor's choices. Other fans have trouble adjusting to sudden changes. Sooner than you might expect, however, the new actor settles in and may even become more popular than the previous one.

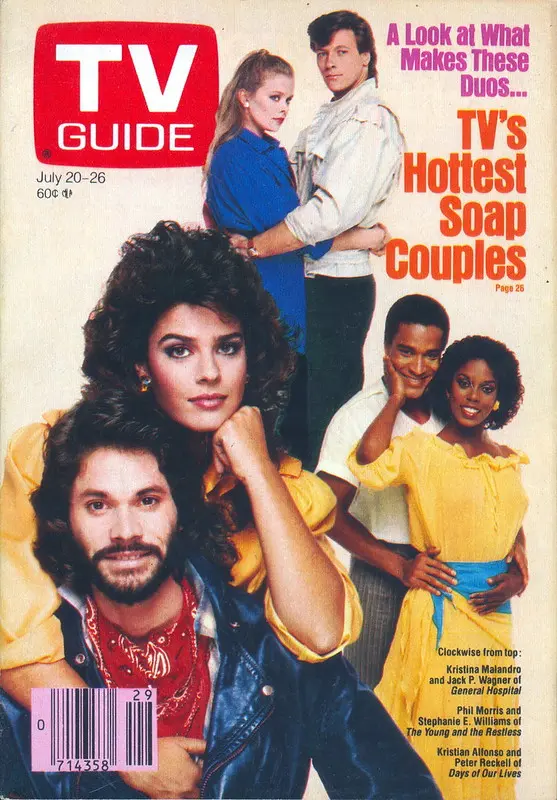

"TV Guide #1686" by trainman (resized) is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

This kind of abrupt casting change can happen any time and with just about any character. For instance, I grew up watching the great soap opera power couple, Bo and Hope Brady (featured in the left-hand corner on the cover of TV Guide above). Peter Reckell was Bo from 1983 to 1992 (from my early girlhood until my teens, the prime years when I was watching the show). Even though Bo was one of the most popular characters on the series, he was replaced with Robert Kelker-Kelly from 1992-1995. I had a great attachment to Peter Reckell, but I gave the new guy a real shot and came to like his portrayal. But while I got used to Kelker-Kelly, others stubbornly insisted that Reckell was the real Bo Brady, and he did return to the role. Even though Bo was written off in 2016, this poll from 2019 shows that diehard fans still have strong opinions one way or the other.

So, what does this have to do with tabletop RPGs? First of all, we all know that the characters who start a campaign won't always make it to the end. They might be killed in action, or a player could want to retire their first character and try another. Some players might have to leave the group, either for a session, intermittently, or for good. New players could hop on board in the middle of epic story arcs. But if we use the soap opera model, none of that matters. The simple fact is that when casting needs to change, it doesn't have to wreck the character or campaign.

A new character can be introduced in a new scene (see below for more on how to do that well), but they don't have to be. Figure out what makes the character distinct and then throw them into the middle of the action. There's no reason to spend a lot of time explaining the whys of the situation. In fact, it could simply be announced when the game first starts: "Tonight, Rich has to work, so Miklos the fighter will be played by Niki. Last time, Ulkar inched closer to becoming a full-fledged Red Wizard..." If the character was mid-scene when the last session ended, let the player start from there. If a new scene is starting, act like the character was always going to be part of it and move forward.

If a player can't make it to a game or two, see if another player would like to take over their character for the session, and not just mechanically. A DM can and should lay out a few guidelines, such as major character traits, and restrictions, such as not sabotaging the character. In exchange, XP can be offered for efforts to add them throughout the session, rather than only using them during combat. If the group has already played together, then everyone has seen how the character is usually portrayed. If a player is up to the challenge, they can take over the character right away, in the middle of ongoing events; the soap opera model shows us that they shouldn't have to wait for a new scene.

This model can also help when a player wants to try a new character instead of continuing with their old one, or if a player leaves the group. If the player wants their old character to be retired and kept out of the action, then the DM should probably try to respect their wishes. Players can have strong feelings about their characters, since they're personal creations. If the player doesn't mind, or if their character is integral to the story, they can become a special NPC. Whenever the character is needed, the DM can step into the role or ask if someone else wants to try it. If a player sticks to the character's loose script, gives them a touch of life, and makes use of their abilities, they should get some kind of reward. If a DM tries this method, they'll probably find the group reacts more to the character and that scenes are more engaging; these outcomes are their own rewards.

There's one more interesting possibility this kind of casting allows for: if the player wants to try a new character, if a new player is learning the ropes, or if someone is joining the group for one session, the DM can offer an existing NPC for a brief run, with the option to take them on permanently. This can be particularly helpful if the player isn't sure what they want to play or if they're going to like a particular type of character. It can also be a good way to give a new player a trial run and see how they gel with the group. The DM can provide a loose script of defining character traits and leave the rest to the player, or work with them on continuing the NPC's established goals. If it doesn't work out, the player can surrender the NPC, leave the game, or start a new character; no harm, no foul.

Brand new characters aren't introduced into a well established soap operas often, so when they are, efforts are made to start them off with a bang. That doesn't mean they're going to show up amidst explosions or gunfights, since most soap operas don't usually feature such action. What it does mean is that things they say and do are going to be noteworthy, if not to the other characters, then to the audience. It could be that something they say raises red flags for fans, who know all of the show's secrets. It might be that they instantly hit it off or make enemies with other characters, which will affect how everyone reacts to them. Perhaps they do something important, like engaging in sabotage or delivering an important message.

Whatever the case, the key is to make the new character conspicuous in the scene so the audience (the players) notices them, whether or not they stand out to the other characters (the NPCs). DMs should usually give a new character a bit more spotlight time. The DM and the player of the new character should look for opportunities to inject some mystery, history, comedy, or suspicion into the way they reveal themselves. The audience should be left wanting to see the character again so they can figure out who they really are and what they really want.

The process starts with a few careful choices that you can make by answering these questions:

What makes the character visually distinctive?

How are they choosing to approach others in the scene?

What's their secret mission?

How are they tied to pre-existing characters?

How do their reactions give clues to their deeper motives?

Players can benefit from answering these questions before introducing new characters into a game. It can also help to know what kind of scene they'll be facing so they can anticipate how their character will fit. Instead of giving long descriptions, players should be encouraged to inject brief descriptions or shift their portrayal at certain times. First, they can quickly cover their character's appearance by focusing on what sets them apart. Then, they might want to describe small ways the character reacts when they feel invested in or threatened by something going on in the scene (or they can show this with in-character roleplay). Shifting your gaze or changing the subject can transmit the idea that the character has some secrets.

Players should be mindful of their character's hidden desires or objectives and look for ways these things can affect what the character says or does. This doesn't mean that players should go out of their way to make their characters act suspiciously all the time; that might make the rest of the characters avoid them. They should highlight what their character intends others to see but leave room for telegraphing inner turmoil the character is experiencing. It's a delicate balance but can make for strong first impressions, interest in future discussions, and a sense that the new kid on the block is a three dimensional person with a lot of potential.

It's not every day that a character gets written off a soap series, so the writers usually go out of their way to make it powerful. Sometimes, they go big and lead up to a dramatic death scene. Maybe there was an attack or an accident; the cause only matters so much. Perhaps the character has been lingering in critical condition or has a sudden heart attack; just how long it takes also doesn't matter a lot, either. What matters most is that the dying character might get to chew up the scene with their final choices, and other characters get to respond. Some hear about it from a distance and try to get to the victim in time to save them or say goodbye. Others are mournful as the news interrupts whatever else is going on in their lives; a few might even be glad to hear a foe has fallen. The characters who are on the scene also have their moment to shine as they react to losing a friend, a lover, a family member, or even an old rival.

But death isn't the only way out. Sometimes, a character decides to leave the area, temporarily or permanently. This usually happens after a major story arc puts them to the test and many of their ongoing problems are resolved. Often, the writers know the character will be leaving in advance and the character makes their intention known ahead of time. Their departure will be preceded by meetings with people of interest to them as they say their goodbyes and take care of any loose ends. They probably won't resolve everything, and lingering ties could pull them back in the future. However, for the moment, a sense of finality is given in their demeanor and statements. Sometimes these scenes are solemn, other times they're full of pleas to stay, but they matter to everyone involved in some way. They're also prime opportunities for characters to share their memories and feelings about recent events.

Characters can also go missing as part of a story. It could be that they've run off, faked their own death, or otherwise pulled up stakes. On the other hand, they could have been abducted and imprisoned, leaving few clues behind to follow. After every effort is made to find them, what else can the rest of the cast do except move on? Being written off like this makes it seem a lot more likely that they'll return once the right clue is revealed or it's dramatically appropriate for them to escape.

Sometimes, though, characters just don't work out and a show doesn't want to deal with resolving them. It could be that the character was a flop with audiences or there's a sudden problem with an actor. If it's going to take too much effort to plausibly get them out of the way and make them stay gone, writing a big farewell just isn't worth it. We've seen this happen on other kinds of shows: a character leaves the scene, or an episode ends, and the show proceeds as if they'd never existed. It doesn't matter if they were frequently seen or front burner characters; they're just gone. This can be hard on an audience's suspension of disbelief at first, but can also bring a sense of relief to fans or those behind the scenes.

So how can this help us in tabletop roleplaying games? If a player knows that they're going to leave a game, they can work with the DM on a way out. If they think they might return, a death can be implied off-screen, the character can choose to leave, or they can vanish under mysterious circumstances that can't be figured out easily. (The last option can be difficult if characters have access to high level magic, but it's not impossible.) If the character probably won't return, then on-screen death or moving them far away can give a sense of finality. Either way, letting the player choose the kind of send-off they'd like to see can be a respectful and caring way to see them off. They should get some more spotlight time in their final scenes and every effort should be made to make those moments memorable.

For the DM, these things can make NPC exits more interesting. While it seems like all NPCs will stay put until the player characters deal with them, it can add a realistic touch to decide to write one of them off every now and then. Even in older eras, people moved or vanished. Giving beloved NPCs an emotional send-off can make the players appreciate them all the more and might spur them to get closer to other NPCs of interest, while they're still around. Moving NPCs can inject a sense of realism into a game, in that these characters are making their own choices and taking action beyond the player characters' desires or reach.

But don't worry; as I'm about to discuss, characters who leave might show up again when you least expect it.

We've seen this in comic books and soap operas for decades: a character is known to be dead - fans might have even watched them die - but somehow, even years later, they return. Any number of reasons can be contrived for this purpose: a doppelganger, mistaken identity, misdiagnosis, and so on. Their comeback is likely going to be riddled with high drama as they struggle with amnesia or some other condition related to their exit. It will definitely affect the emotions of characters who were tied to them and believed them to be gone for good. But writers spend years building up these characters and fans tend to be heavily invested in them - so why let all of that go to waste? While most soap operas are real-world stories with real life restrictions, they show us that reality can be bent when it's dramatically appropriate.

Even characters who left of their own free will and seemed to be done with the city might find a reason to go back. This kind of return can be infused with reluctance, disgust, and dismay on the character's part. They might even plan to leave again as soon as their business is done - but just when they think they've found a way out, something else pulls them back in. This can add a level of realism to characters, whether they're PCs or NPCs. Not everyone wants to revisit their old stomping grounds or deal with the times in their lives those places represent. Not everyone feels like they have a choice about returning to a situation, a family, or a house that they left behind. Some crawl back when they have nowhere else to go, or after they tried to set up shop somewhere else but it didn't work out.

In tabletop games, as in many other types of stories, bringing back characters that have been written off should be done sparingly and with careful consideration. If everyone keeps coming back from the dead, then death will certainly lose its gravity. Games like D&D help with this in various ways; the Resurrection spell's description states that the soul has to "be free and willing" to be revived. It's likely that souls which go to the realms of their gods and enjoy their afterlives will want to stay there; only some will give up their reward for another shot at their old life.

A legacy character is born on the show and seen at various life stages. They may have been born as part of a story arc and introduced as infants or their recent birth was mentioned prominently in conversation. From that point on, they're part of the series, mentioned by the characters and brought on screen every so often as they grow up. They probably get more screen time if they're in a core family, but only so much when they're small. (In many soaps, child characters don't stay children for very long; they're quickly aged until they're teens and the timeline of the show is quietly bent to allow for that. Then, they become the center of their own intrigues. This is amusingly known as Sudden Onset Rapid Aging Syndrome.) It can make fans feel more invested when they're watching generations of a family advance in life, and they can become deeply attached to legacy characters in particular.

But one of the greatest things about legacy characters is that they form the foundation of the next generation of personalities on the show. While brand new characters are added from time to time, most of the offspring of established characters will stick around to enjoy the spotlight. They carry on family names and reputations, pick up old feuds, and take on responsibilities, as they were born to do. The writers don't have to wrack their brains for new people to weave into the series; they can use characters that have been waiting in the background for years.

Once again, this can be carried over into your tabletop roleplaying campaigns. If you really don't want to have player character romances in your games, that's fine. NPCs can be shown with their children. If PCs can have relationships and children, they can have new kids during downtime or in the background of the main adventure. I'm not suggesting gamers should do what soaps do with chronology. Aging children suddenly can be more awkward in games. But advancing the timeline of a campaign can be done just by figuring out a number of months or years of downtime that you'd like to skip over. The DM should ask players for a few key projects their characters would pursue in that time, and then sum up how it went. It's ideal to do this at the end of major story arcs, when characters would probably want to relax for a while.

Allowing a campaign to cover years and even decades of time in-game can be richly rewarding for everyone. Players will get to see who their characters become as they age, and DMs will get to figure out how to advance the setting in ways that make sense. And if it sounds fun, players can decide to retire their original characters and start playing their offspring. This is a powerful experience because it creates the sense of a family saga. And, as we'll soon discuss, the family saga is one of the most potent storytelling aspects soap operas offer.

<< Soap Opera Character-Building Soaps & Story Creation >>

Latest Updates